Considerations for

PBC Patient Care

Pathway

This website is for educational purposes only and provides a non-exhaustive description of potential care options in PBC based on peer-reviewed literature. HCPs should exercise their independent clinical judgment when selecting care options for a particular patient. This educational material does not promote the use of any particular care option.

Get startedThis educational resource was developed and is provided by Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

us-PB-MED-00921 08/2023

It looks like your browser window may be too small to display this site.

Please try accessing on a larger screen, zooming out, or expanding your browser.

Considerations for

PBC Patient Care

Pathway

This website is interactive. For information tailored to your practice, please select relevant criteria on as many or as few pages as you would like. The content provided is based on information from approved product prescribing information, published guidelines, and peer-reviewed literature.

If requested, this material is available through a Medical Information Request Form.

This educational resource was developed and is provided by Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

us-PB-MED-00921 08/2023

Pathway overview

Choose a starting point on the patient pathway.

Suspected PBC

Elevated ALP AND

AMA Positive

No

Additional Testing Differential Diagnosisand Fibrosis Staging

Continue

Treatment

Yes

Adequate Response?

No

Continue

Treatment

Yes

Adequate Response?

No

This educational resource was developed and is provided by Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

us-PB-MED-00921 08/2023

For patients with high risk,

refer to a hepatologist or

transplant center.

Adequate

Response?

No

Adequate

Response?

Continue Treatment

Yes

Continue Treatment

Yes

No

Pre-diagnosis

diagnosis

1ST-LINE TREATMENT

2nd-line treatment

Patient assessment and baseline measurements

Patient with suspected PBC:

Select all that apply.

Laboratory testing for consideration

The following testing is not all required routinely (or in all patients) for diagnosing PBC, but may be used in AMA-negative cases and at initial assessment to rule out other causes for symptoms and/or achieve baseline measurements.

Select all that apply.

*Key considerations for PBC diagnosis and management, not comprehensive of all measures included in laboratory testing.

Liver biopsies are rarely needed to diagnose PBC but may be recommended in AMA-negative patients with the absence of PBC-specific autoantibodies, or to rule out concomitant AIH, NASH or other liver diseases.1-3

Evidence of portal hypertension include ascites, gastroesophageal varices, or persistent thrombocytopenia.9

Noninvasive imaging tests (TE, MRE) can identify patients with advanced fibrosis and at risk of hepatic decompensation.10

LSM by VCTE, in combination with established biochemical criteria of therapeutic response or prognostic score, improves outcome prediction in PBC.11

Imaging and serology

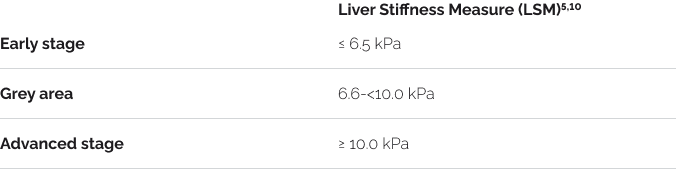

Transient elastography

Transient elastography is not necessarily needed for diagnosis of PBC but can serve as a baseline to assess the degree of fibrosis, even in the absence of cirrhosis, in patients with PBC.2,3

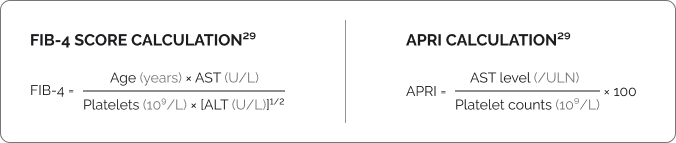

The FIB-4 and APRI

FIB-4 and APRI are not directly linked to diagnosing a patient, but more so to establish the fibrosis assessment and prediction of prognosis in PBC once the diagnosis of PBC has been established.9

ULN = Upper limit of normal.

Routine physical examination4

- Hepatomegaly (enlarged liver)1-4

- Splenomegaly2-4

- Extrahepatic signs of advanced liver disease:

- Icterus of sclera, skin and mucous membranes2-3

- Hyperpigmentation1

- Xanthoma1 (yellowish cholesterol/fatty deposits) and xanthelasma1-4 (deposits on eyelids)

- Palmar and plantar erythema2-3

- Nail abnormalities2-3

- Excoriations1-3

- Spider angioma/telangiectasia, edema, ascites or splenomegaly may be found in setting of portal hypertension1

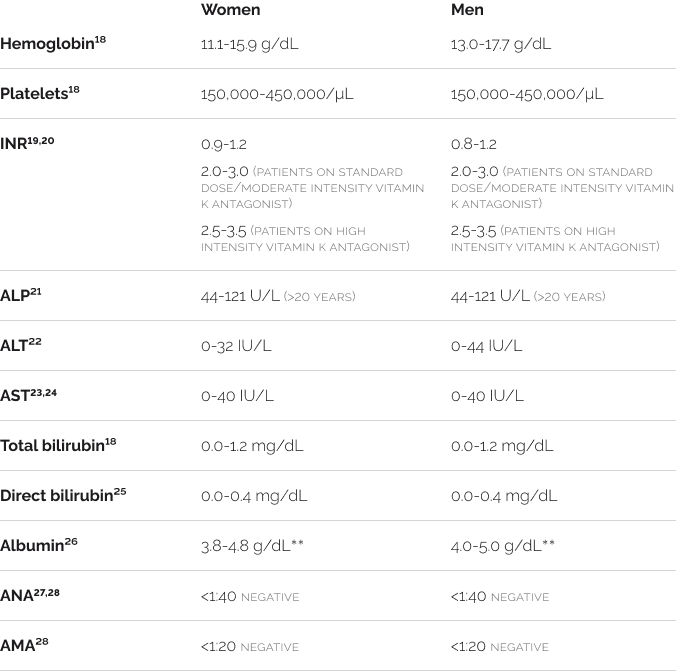

Typical ranges for laboratory tests*

*Reference intervals may vary based on lab/institution. Values provided are per LabCorp. LabCorp does not separate reference intervals by age group and sex for most adult tests.**Albumin reference ranges vary by age and sex. Reported values are for ages 31 to 50 years.

Differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of PBC should be suspected in adult patients with chronic liver test abnormalities, after exclusion of other causes of liver disease,1,3 including, but not limited to:

Select all that apply.

Note: AMA positivity alone is not sufficient to make the diagnosis of PBC.1-3 Guidelines recommend following up with these patients every 6-12 months with repeat liver enzyme panels.2

Diagnosis of PBC

The diagnosis of PBC should be suspected in adult patients with chronic cholestasis after exclusion of other causes of liver disease.1,3 While the available guidelines differ slightly in recommendations for patients with suspected PBC who are AMA-negative, the guidelines listed below agree that a PBC diagnosis can be established in patients with1,3:

*AMA positive = immunofluorescent assay titer of >1:40 or EIA >25 units.2,3

Note: AMA positivity alone is not sufficient to make the diagnosis of PBC.1-3 Guidelines recommend following up with these patients every 6-12 months with repeat liver enzyme panels.2

Additional scenarios and considerations for diagnosing PBC based on available guidelines:

Select all that apply.

Goals of PBC therapy

The treatment goals of PBC are aimed to prevent progression to advanced liver disease and to alleviate symptoms.1-4,12

Select all that apply.

Baseline assessment: risk of disease progression

Assessing baseline risk ensures patients receive timely follow-up and allows for a personalized treatment approach.

Pre-treatment risk assessment:

Select all that apply.

LOW RISK

EMERGING DATA

Intermediate-high risk

Consider referral to a hepatologist or transplant center for further assessment

Note: Emerging data from peer-reviewed, primary research literature; not incorporated in guidelines.

Initiation of first-line treatment considerations

Initiate 1st-line treatment

Select all that apply.

Per discretion of provider:

See warnings and precautions for UDCA. →

Continue to monitoring

Routinely monitor for biochemical response, tolerability, and progression of PBC14

Select all that apply.

Per discretion of provider:

Binary criteria and definition of response1,2

Risk scoring systems1-3

Select all that apply.

See continuous scoring calculators. →

Routine follow-up assessments should look for1-3,14

Select all that apply.

Per discretion of provider:

Discontinuing treatment should be considered in patients with increased GGT, ALP, AST, ALT, bilirubin.14

Note: The content of this page is based on information from UDCA PI14 and published guidelines.1-3

Fibrosis stage (as assessed by VCTE or MRE) can guide the decision of whether response to UDCA and subsequent second-line treatment need should be assessed at 6 months or 12 months.10

Contraindicated in patients with14:

- complete biliary obstruction

- known hypersensitivity or intolerance to ursodiol or any components of the formulation

Patients with the following should receive appropriate specific treatment14:

- Variceal bleeding

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Ascites

- In need of an urgent liver transplant

Relevant pages

Combining LSM by VCTE with prognostic scores, such as GLOBE score, provides more accurate risk assessment than prognostic scores alone.11

Relevant pages

If there is intolerance or no response, evaluate for or initiate 2nd-line treatment.

To report suspected adverse reactions, contact Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. or the FDA:

Routine monitoring assessments for first-line treatment

Routine follow-up assessments should look for1-3,14

Select all that apply.

All chronic liver disease patients2

Select all that apply.

Laboratory testing for consideration when conducting ongoing monitoring and assessments1-6

Select all that apply.

*Key considerations for PBC diagnosis and management, not comprehensive of all measures included in laboratory testing.

If advanced liver disease is present, evaluate for liver transplantation.2

Evidence of portal hypertension includes ascites, gastroesophageal varices or persistent thrombocytopenia.9

Continuous scoring calculators

UK-PBC Score 1-3,30

The UK-PBC Risk Score is used for patients with PBC at any stage to estimate the risk, as a percentage, that the patient will experience liver transplantation and liver-related death. Calculation is based on patient’s total bilirubin, ALT or AST, and ALP after 12 months of therapy; albumin and platelets.1-3,30

Assess your patient’s UK-PBC Score →

GLOBE Score 1-3,31

Calculation is based on patient’s age, total bilirubin, ALP, albumin, platelets.1-3,31

Assess your patient’s GLOBE Score →

MAYO Score2,3,32

Calculation is based on patient’s age, bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, peripheral edema status, diuretic therapy usage.2,3,32

Combining LSM by VCTE with prognostic scores, such as GLOBE score, provides more accurate risk assessment than prognostic scores alone.11

ACG/CLDF guidelines recommend calculating the Mayo score for all PBC patients.2

UDCA warnings and precautions

- Patients with variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites or in need of an urgent liver transplant, should receive appropriate specific treatment.

- Liver function tests (γ-GT, alkaline phosphatase, AST, ALT) and bilirubin level should be monitored. Treatment discontinuation should be considered if parameters increase to a level considered clinically significant in patients with stable historical liver function test levels.

- Caution should be exercised to maintain patients’ bile flow.

Response and on-treatment risk stratification

Despite treatment with UDCA, PBC can remain a progressive disease and has a risk of liver-related complications and death. The risk of developing end-stage complications and potential need for additional treatments should be assessed in all patients.3

Assess risk of progression based on response to treatment1,2,4,10,13

Select all that apply.

LOW RISK4/ADEQUATE RESPONSE TO UDCA

EMERGING DATA

INTERMEDIATE-HIGH RISK4/INTOLERANCE OR INADEQUATE RESPONSE TO UDCA1 (based on established criteria)

OR ALP:

OR BILIRUBIN:

OR ALBUMIN

EMERGING DATA

CONSIDER REFERRAL FOR FURTHER ASSESSMENT4

Note: Emerging data from peer-reviewed, primary research literature; not incorporated in guidelines.

For low-risk patients, continue 1st-line treatment and assess response every 3-6 months.1

Combining LSM by VCTE with prognostic scores, such as GLOBE score, provides more accurate risk assessment than prognostic scores alone.11

For intermediate- to high-risk patients, evaluate risk-benefit of continuing to 2nd-line treatment or referring to a hepatologist or transplant center for further assessment.4

Relevant pages

Second-line treatment considerations

Options for 2nd-line treatment10

Select all that apply.

Initiate 2nd-line treatment1-3

Select all that apply.

See boxed warning for obeticholic acid. →

Continue to monitoring

Routinely monitor for biochemical response, tolerability, and progression of PBC16

Select all that apply.

Per discretion of provider:

Closely monitor patients with16:

Select all that apply.

For:

If intolerance occurs

If there is intolerance due to pruritus,16 consider:

Select all that apply.

Discontinue treatment in patients who16:

- Develop evidence of hepatic decompensation

- Have compensated cirrhosis and develop evidence of portal hypertension

- Experience clinically significant hepatic adverse reactions

- Develop complete biliary obstruction

- Have persistent, intolerable pruritus

Refer these patients to a hepatologist or transplant center.

Note: The content of this page is based on information from obeticholic acid PI16 and published guidelines.1-3

Obeticholic acid is contraindicated in patients with16:

- decompensated cirrhosis (e.g., Child-Pugh Class B or C) or prior decompensation event

- compensated cirrhosis, who have evidence of portal hypertension (e.g., ascites, gastroesophageal varices, persistent thrombocytopenia)

- complete biliary obstruction

Fibrates are discouraged in patients with decompensated liver disease.17

Fenofibrate is contraindicated in patients with17:

- Known hypersensitivity to fenofibrate

- Liver disease

- Severe renal dysfunction

- Preexisting gallbladder disease

- Breastfeeding

If fibrates are used, the following monitoring should be considered17:

- Kidney function (uric acid, BUN, creatinine clearance)

- Hepatic function

- CPK

- Platelets, WBC

- Lipid panel: total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides

Relevant pages

Relevant pages

Relevant pages

To report suspected adverse reactions, contact Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. or the FDA:

Additional pruritus management

Strategies to manage pruritus in obeticholic acid-treated patients

Select all that apply.

Topical treatments and lifestyle interventions

Prescription medications

Other therapies*

*These physical interventions are available as salvage therapies.

If steps to manage pruritus are not successful16:

Select all that apply.

Ocaliva boxed warning

WARNING: HEPATIC DECOMPENSATION AND FAILURE IN PRIMARY BILIARY CHOLANGITIS PATIENTS WITH CIRRHOSIS16

See full prescribing information → for complete boxed warning.

- Hepatic decompensation and failure, sometimes fatal or resulting in liver transplant, have been reported with OCALIVA treatment in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) patients with either compensated or decompensated cirrhosis.

- OCALIVA is contraindicated in PBC patients with decompensated cirrhosis, a prior decompensation event, or with compensated cirrhosis who have evidence of portal hypertension.

- Permanently discontinue OCALIVA in patients who develop laboratory or clinical evidence of hepatic decompensation; have compensated cirrhosis and develop evidence of portal hypertension; or experience clinically significant hepatic adverse reactions while on treatment.

Ocaliva Indication and additional important safety information

Indication

- OCALIVA, a farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist, is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis who do not have evidence of portal hypertension, either in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) with an inadequate response to UDCA or as monotherapy in patients unable to tolerate UDCA.

- This indication is approved under accelerated approval based on a reduction in alkaline phosphatase (ALP). An improvement in survival or disease-related symptoms has not been established. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

Contraindications

OCALIVA is contraindicated in patients with:

- decompensated cirrhosis (e.g., Child-Pugh Class B or C) or a prior decompensation event.

- compensated cirrhosis who have evidence of portal hypertension (e.g., ascites, gastroesophageal varices, persistent thrombocytopenia).

- complete biliary obstruction.

Warnings and Precautions

Hepatic Decompensation and Failure in PBC Patients with Cirrhosis

- Hepatic decompensation and failure, sometimes fatal or resulting in liver transplant, have been reported with OCALIVA treatment in PBC patients with cirrhosis, either compensated or decompensated. Among postmarketing cases reporting it, median time to hepatic decompensation (e.g., new onset ascites) was 4 months for patients with compensated cirrhosis; median time to a new decompensation event (e.g., hepatic encephalopathy) was 2.5 months for patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Some of these cases occurred in patients with decompensated cirrhosis when they were treated with higher than the recommended dosage for that patient population; however, cases of hepatic decompensation and failure have continued to be reported in patients with decompensated cirrhosis even when they received the recommended dosage.

- Hepatotoxicity was observed in the OCALIVA clinical trials. A dose-response relationship was observed for the occurrence of hepatic adverse reactions including jaundice, worsening ascites, and primary biliary cholangitis flare with dosages of OCALIVA of 10 mg once daily to 50 mg once daily (up to 5-times the highest recommended dosage), as early as one month after starting treatment with OCALIVA in two 3-month, placebo-controlled clinical trials in patients with primarily early stage PBC.

- Routinely monitor patients for progression of PBC, including hepatic adverse reactions, with laboratory and clinical assessments to determine whether drug discontinuation is needed. Closely monitor patients with compensated cirrhosis, concomitant hepatic disease (e.g., autoimmune hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease), and/or with severe intercurrent illness for new evidence of portal hypertension (e.g., ascites, gastroesophageal varices, persistent thrombocytopenia) or increases above the upper limit of normal in total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, or prothrombin time to determine whether drug discontinuation is needed. Permanently discontinue OCALIVA in patients who develop laboratory or clinical evidence of hepatic decompensation (e.g., ascites, jaundice, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy), have compensated cirrhosis and develop evidence of portal hypertension (e.g., ascites, gastroesophageal varices, persistent thrombocytopenia), experience clinically significant hepatic adverse reactions, or develop complete biliary obstruction. If severe intercurrent illness occurs, interrupt treatment with OCALIVA and monitor the patient’s liver function. After resolution of the intercurrent illness, consider the potential risks and benefits of restarting OCALIVA treatment.

Severe Pruritus

- Severe pruritus was reported in 23% of patients in the OCALIVA 10 mg arm, 19% of patients in the OCALIVA titration arm, and 7% of patients in the placebo arm in a 12-month double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial of 216 patients. Severe pruritus was defined as intense or widespread itching, interfering with activities of daily living, or causing severe sleep disturbance, or intolerable discomfort, and typically requiring medical interventions. Consider clinical evaluation of patients with new onset or worsening severe pruritus. Management strategies include the addition of bile acid-binding resins or antihistamines, OCALIVA dosage reduction, and/or temporary interruption of OCALIVA dosing.

Reduction in HDL-C

- Patients with PBC generally exhibit hyperlipidemia characterized by a significant elevation in total cholesterol primarily due to increased levels of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C). Dose-dependent reductions from baseline in mean HDL-C levels were observed at 2 weeks in OCALIVA-treated patients, 20% and 9% in the 10 mg and titration arms, respectively, compared to 2% in the placebo arm. Monitor patients for changes in serum lipid levels during treatment. For patients who do not respond to OCALIVA after 1 year at the highest recommended dosage that can be tolerated (maximum of 10 mg once daily), and who experience a reduction in HDL-C, weigh the potential risks against the benefits of continuing treatment.

Adverse Reactions

- The most common adverse reactions (≥5%) are: pruritus, fatigue, abdominal pain and discomfort, rash, oropharyngeal pain, dizziness, constipation, arthralgia, thyroid function abnormality, and eczema.

Drug Interactions

Bile Acid Binding Resins

- Bile acid binding resins such as cholestyramine, colestipol, or colesevelam adsorb and reduce bile acid absorption and may reduce the absorption, systemic exposure, and efficacy of OCALIVA. If taking a bile acid-binding resin, take OCALIVA at least 4 hours before or 4 hours after taking the bile acid-binding resin, or at as great an interval as possible.

Warfarin

- The International Normalized Ratio (INR) decreased following coadministration of warfarin and OCALIVA. Monitor INR and adjust the dose of warfarin, as needed, to maintain the target INR range when co-administering OCALIVA and warfarin.

CYP1A2 Substrates with Narrow Therapeutic Index

- Obeticholic acid may increase the exposure to concomitant drugs that are CYP1A2 substrates. Therapeutic monitoring of CYP1A2 substrates with a narrow therapeutic index (e.g., theophylline and tizanidine) is recommended when co-administered with OCALIVA.

Inhibitors of Bile Salt Efflux Pump

- Avoid concomitant use of inhibitors of the bile salt efflux pump (BSEP) such as cyclosporine. Concomitant medications that inhibit canalicular membrane bile acid transporters such as the BSEP may exacerbate accumulation of conjugated bile salts including taurine conjugate of obeticholic acid in the liver and result in clinical symptoms. If concomitant use is deemed necessary, monitor serum transaminases and bilirubin.

View full prescribing information, including Boxed Warning. →

To report suspected adverse reactions, contact Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. or the FDA:

Routine monitoring assessments for second-line treatment

Patients with cirrhosis (even if not advanced) on obeticholic acid should be carefully monitored for evidence of liver decompensation or portal hypertension.9

Routine follow-up assessments should look for1-3,6

Select all that apply.

All chronic liver disease patients2

Select all that apply.

Laboratory testing for consideration when conducting ongoing monitoring and assessments1-6

Select all that apply.

*Key considerations for PBC diagnosis and management, not comprehensive of all measures included in laboratory testing.

If advanced liver disease is present, evaluate for liver transplantation.2

Evidence of portal hypertension includes ascites, gastroesophageal varices or persistent thrombocytopenia.9

For patients who do not respond to obeticholic acid after 1 year at the highest recommended dosage that can be tolerated (maximum of 10 mg once daily), and who experience a reduction in HDL-C, weigh the potential risks against the benefits of continuing treatment.16

Final results

This website is for educational purposes only and provides a non-exhaustive description of potential care options in PBC based on peer-reviewed literature. HCPs should exercise their independent clinical judgment when selecting care options for a particular patient. This educational material does not promote the use of any particular care option.

- Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary biliary cholangitis: 2018 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69(1):394-419.

- Younossi Z, Bernstein D, Shiffman ML, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary biliary cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(1):48-63.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: the diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-172.

- Hirschfield GM, Chazouillères O, Cortez-Pinto H, et al. A consensus integrated care pathway for patients with primary biliary cholangitis: a guideline-based approach to clinical care of patients. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(8):929-939.

- Cristoferi L, Calvaruso V, Overi D, et al. Accuracy of transient elastography in assessing fibrosis at diagnosis in naïve patients with primary biliary cholangitis: a dual cut-off approach. Hepatology. 2021;74(3):1496-1508.

- Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723-750.

- Piratvisuth T, Tanwandee T, Thongsawat S, et al. Multimarker panels for detection of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective, multicenter, case-control study. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6(4):679-691.

- Callichurn K, Cvetkovic L, Therrien A, Vincent C, Hétu PO, Bouin M. Prevalence of celiac disease in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2021;4(1):44-47.

- Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary biliary cholangitis: 2021 practice guidance update from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 24]. Hepatology. 2021;10.1002/hep.32117.

- Kowdley KV, Bowlus CL, Levy C, et al. Application of the latest advances in evidence-based medicine in primary biliary cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;00:1-11.

- Corpechot C, Carrat F, Gaouar F, et al. Liver stiffness measurement by vibration-controlled transient elastography improves outcome prediction in primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2022;77(6):1545-1553.

- Murillo Perez CF, Harms MH, Lindor KD, et al. Goals of treatment for improved survival in primary biliary cholangitis: treatment target should be bilirubin within the normal range and normalization of alkaline phosphatase. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(7):1066-1074.

- Murillo Perez CF, Hirschfield GM, Corpechot C, et al. Fibrosis stage is an independent predictor of outcome in primary biliary cholangitis despite biochemical treatment response. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(10):1127-1136.

- URSO® 250, URSO® FORTE (ursodiol) [Full Prescribing Information]. Allergan, Inc. Madison, NJ.

- Gerussi A, Bernasconi DP, O'Donnell SE, et al. Measurement of gamma glutamyl transferase to determine risk of liver transplantation or death in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(8):1688-1697.e14.

- OCALIVA® (obeticholic acid) [Full Prescribing Information]. Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. New York, NY.

- Sidhu G, Tripp J. Fenofibrate. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; June 28, 2021.

- Critical values. October 24, 2022. Accessed May 31, 2023. Available at: https://files.labcorp.com/labcorp-d8/2022-12/Panic_%28Critical%29_Values_10-24-2022.pdf.

- Prothrombin Time Sample Report. Accessed April 11, 2023. Available at: https://www.labcorp.com/tests/005199/prothrombin-time-pt.

- Prothrombin Time, Serial Sample Report. Accessed May 31, 2023. Available at: https://files.labcorp.com/testmenu-d8/sample_reports/485199.pdf.

- Alkaline phosphatase. Accessed May 31, 2023. Available at: https://www.labcorp.com/tests/001107/alkaline-phosphatase.

- New ALT reference intervals for children and adults. LabCorp. Accessed May 31, 2023. Available at https://www.labcorp.com/assets/5286.

- Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) Sample Report. Accessed April 11, 2023. Available at: https://www.labcorp.com/tests/001123/aspartate-aminotransferase-ast-sgot.

- Hepatic Function Panel Sample Report. Accessed June 1, 2023. Available at: https://files.labcorp.com/testmenu-d8/sample_reports/322755.pdf.

- Bilirubin, Direct. Accessed April 25, 2023. Available at: https://www.labcorp.com/tests/001222/bilirubin-direct.

- Albumin. Accessed June 1, 2023. Available at: https://www.labcorp.com/tests/001081/albumin.

- ANA 12 Sample Report. Accessed June 1, 2023. Available at: https://files.labcorp.com/testmenu-d8/sample_reports/520188.pdf.

- PBC Profile Sample Report. Accessed June 1, 2023. Available at: https://files.labcorp.com/testmenu-d8/sample_reports/520192.pdf.

- Kasarala G, Tillmann HL. Standard liver tests. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;8(1):13-18.

- UK-PBC Score Calculator. Accessed April 28, 2023. Available at: https://www.mdapp.co/uk-pbc-risk-score-calculator-360/

- The Global PBC Study Group. The GLOBE score for patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Accessed April 25, 2023. Available at: https://www.globalpbc.com/globe

- Mayo Clinic. The updated natural history model for primary biliary cholangitis. Mayo Calculator. Accessed at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/transplant-medicine/calculators/the-updated-natural-history-model-for-primary-biliary-cholangitis/itt-20434724

- Murillo Perez CF, Ioannou S, Hassanally I, et al. Early identification of insufficient biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Poster 1266 presented at: 2021 AASLD The Liver Meeting; November 12-15, 2021; Virtual.

- Pate J, Gutierrez JA, Frenette CT, et al. Practical strategies for pruritus management in the obeticholic acid-treated patient with PBC: proceedings from the 2018 expert panel. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6(1):e000256.

- Iluz-Freundlich D, Uhanova J, Van Iderstine MG, Minuk GY. The impact of primary biliary cholangitis on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;33:565-570.

- Chapman J, Goyal A, Azevado Am. Splenomegaly. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. June 26, 2023. Accessed October 19, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430907/

- Augustine A, John R, Simon B, Chandramohan A, Keshava SN, Eapen A. Imaging approach to portal hypertension. J Gastrointestinal Abdominal Radiol. 2023:6:123-137.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis A questions and answers for health professionals. September 27, 2023. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/havfaq.htm#general

- Ramirez JC, Ackerman K, Strain SC, Ahmed ST, de los Santos M, Sear D. Hepatitis A and B screening and vaccination rates among patients with chronic liver disease. Hum Vaccin lmmunother. 2016;12(1):64-69.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening and testing recommendations for chronic hepatitis B virus infection (HBV). March 28, 2022. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/testinqchronic.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing recommendations for hepatitis C virus infection. July 13, 2023. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/guidelinesc.htm

- Del Poggio P, Mazzoleni M. Screening in liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006:12(33):5272-5280.

- HBV Primary Care Workgroup. Hepatitis B management: guidance for the primary care provider. February 25, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2023. https://www.hepatitisb.uw.edu/page/primary-care-workgroup/guidance

- Thuluvath, PF, Triger DR, Manku MS, et al. Evening primrose oil in the treatment of severe refractory biliary pruritus. lnpharma Weekly. 1991;778:15.

- Immunize.org. Hepatitis A: Questions and Answers. September 11, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.immunize.org/wp-content/uploads/catg.d/p4204.pdf.